‘Beyond the Dunes’ 2020

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 cm

£395

Sold.

‘Beyond the Dunes’ 2020

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 cm

£395

Sold.

‘Eggs and Doorknob’ 2020

Oil on board

13 x 18 cm

£425

To purchase this painting, please direct your inquiry to Sydney Peterson at thegallery@greenandstone.com

‘The Carousel’

Oil on board

20 x 20 cm

£325

To purchase this painting, please direct your inquiry to Sydney Peterson at thegallery@greenandstone.com

‘Ices on the Lower Mall’

Oil on board

20 x 20 cm

£325

To purchase this painting, please direct your inquiry to Sydney Peterson at thegallery@greenandstone.com

‘And So It Happened’ 2020

Oil on panel

30 x 26 cm

£595

To purchase this painting, please direct your inquiry to Sydney Peterson at thegallery@greenandstone.com

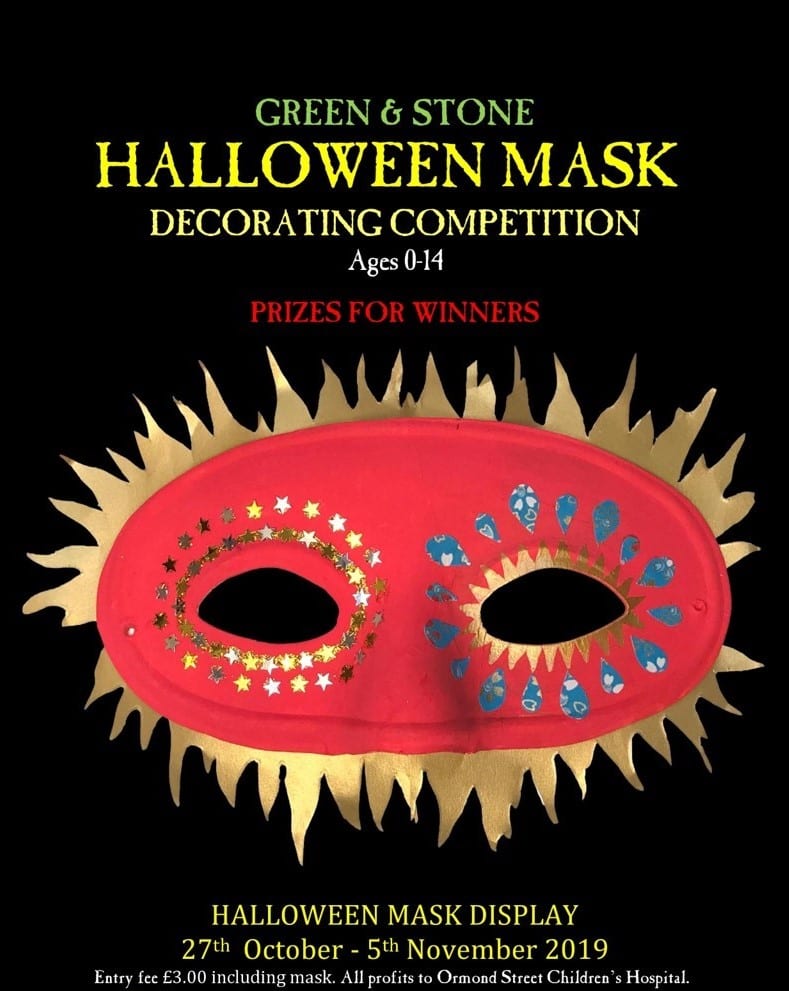

£3.00 per entry including blank mask (2 designs available)

Masks and entry form available at our shop.

Please label the mask with the artist’s name and return the completed mask with entry form by 6pm on Saturday 26th October.

Masks will be on display until 5th November. Please collect the masks from Wednesday 6th November – Sunday 24th November 2019.

A prize for the winner in four age groups:

Ages 0-4 – Art Materials

Ages 5-8 – Green & Stone Gift Voucher

Ages 9-11 – Green & Stone Gift Voucher

Ages 12-14 – Green & Stone Gift Voucher

Prizes will be announced on 31st October!

Am I just a tiny speck of pigment on the end of a cosmic paintbrush?

Why am I really doing this, thirty years on?

How did I end up involved in conceptual abstraction when all I truly want to do is paint dog portraits?

How do I capture with a pencil the sense every night of staring into the deep dark void?

Am I still desperately trying to please Mother?

*

These questions bother all artists, young and old, but there is another, one less existential, and more practical – is it at all significant which oil I use when painting? If you are a watercolourist, no, if you are an oil painter, yes! Ho ho!

The oils we will talk of are vegetable oils which have the desirable property of drying to form a tough adhesive film whilst suspending pigments in a stable solution. Once dry the process is irreversible and the oil cannot be reversed to its original state by any means. These oils, namely linseed, poppy, and walnut, allow the painter to paint.

Crude oil makes the world go round, linseed oil lets the people paint its spin.Linseed oil is pressed the from the seeds of the flax plant which has delicate lilac flowers and which is also used to make linen. So, this excellent plant singlehandedly provides the backbone to an oil painter’s life. God bless you little flowering thing, how lucky we are to have you on this here Earth! For good reason linseed oil is everyone’s starter oil, it is not only glossy and reasonably fast drying, it is trustworthy, tough, and flexible.

Nowadays linseed oil is produced on a huge scale as part of a highly developed modern industry. The oil is normally extracted by crushing the seed and pressing it with the aid of steam. It is used in everything from food, health supplements, furniture care, and of course, artists’ materials. Unlike poppy and walnut oil, linseed oil comes in a plethora of forms, whether in the form of refined, cold-pressed, sun-dried, or stand oil.

The first form of linseed oil to mention is the standard refined linseed oil which is made by crushing and pressing flax seed with the aid of steam. This industrial method helpfully reduces the cost of production. It is an excellent all round glossy oil good for making your own paints, painting with, and making glazes. However, it is not without criticism, some, notably Ralph Mayer, the highly reputable and marvellous investigator of all things painterly wrote that whilst economical, refined oil, or hot-pressed, is inferior to cold-pressed oil, because the steam is so efficient that it extracts other, less desirous, substances that cannot be removed by however much refining. According to Mayer, linseed oil’s heyday was the good old 19th century when all was good, nothing was bad (…?), and canvases had not been dessicrated by steamed paint. Mayer also wrote that refined oil was more prone to brittleness than cold-pressed. With the greatest respect to Ralph Mayer times have changed since his book was published in 1940. Modern technology and alkali refining techniques have redressed the balance of the quality issue, meaning it is highly likely that the difference between hot and cold-pressed is negligible.

Importantly, whilst refined linseed oil looks pale, it has been bleached, so as with most other linseed oils it will, over the years, revert to its yellow state. When old, linseed oil gives a warm glow to a painting. This patina, depending on the individual is either positive or negative. Personally, I think it is rather nice, and think it is the answer to my rather simple judgement that old paintings are better than new ones. This factor of yellowing is therefore very important to the oil painter! It is advisable that when using whites, pale colours or light blues consider alternatives to linseed oil.

Refined linseed oil has two more mature cousins, linseed stand oil, and sun-thickened linseed oil. Stand oil is linseed oil heated to 273-300 celsius for several hours with nothing being added or taken away. This heavy, viscous oil looks like a pale honey and is often found in stumpy metal tins whose purpose I cannot claim to know. This oil requires a little more effort from the painter in that to use it one must thin it with turpentine. When cut with turps it is unlike other linseed oils as it is practically non-yellowing. It is ideal for painting smooth, enamel-like films free from brush marks and full of vibrance and life. However, It is only to be used for painting and glazes, not paint grinding.

Similar to stand oil is sun-thickened linseed oil. This oil is also thick and honey-like, however it is not readily sold though making it is relatively easy and inexpensive. This form of oil, like stand oil, is ideal for forming light, almost invisible glazes of colour, delicate, soft shadows or wonderful areas of luminosity. Indeed, if you sadly find yourself in the scenario where you have a rather dull patch on a painting the effect of sun-thickened oil or stand oil mixed with a transparent colour can be astounding. To make your own sun-thickened linseed oil pour some refined linseed oil into a glass container, place a glass lid over the top supported by a few match sticks so air can get in and out, put the container on a window-sill or work bench, give the oil a little stir from time to time, say every other day, and when you have a consistency similar to a thick honey you can use it as you like. As they say, homemade is best! So, if you are one for delicate, luminescent glazes and smooth films, use either of these versions of linseed oil.

As mentioned linseed oil is not the only oil to paint with. Indeed, If you are a forger of 15th century paintings linseed oil is definitely not for you as it did not find popularity until later in the millenium. Instead, the oil of the delicate and creamy walnut is more recommendable, though I do not encourage artistic fraudulence, or do I…? (***ThE aRt MaRKeT iS a cOn!***) The red-turbaned, palid-skinned genius behind the world’s most famous mirror trickery, the one and only Jan van Eyck was a real fan, notoriously saying on his deathbed in July 1441 “Damn, what an oil!”. Oh Jan, blaspheming on your deathbed like that is not a good idea! Enough digressing… By the time of the 15th century most artists had had enough of egg tempera and had moved on to walnut oil. As an oil it was and is often preferred as a binder for whites as it yellows less than linseed oil, meaning paler and colder colours mixed with it change less when dry. It is often remarked that walnut oil has a distinct texture and flow, silkier, and softer than that of other oils and the effect of this is evidenced by the works of masters like van Eyck whose works is indeed, silky, soft and ravishingly detailed. If you are one who enjoys painting on wooden panels with brilliantly glossy paint then walnut oil is very much for you.. This unique creaminess and coolness could be just what you have been looking for after all these years!

Poppy oil is similar to walnut oil in that it does not yellow like linseed oil does (this is why white paint is commonly made with these oils). Poppy oil is naturally colourless or lightly straw coloured and gives a brilliant appearance to a painting. Unlike the other oils, poppy oil dries matt and has a very slow dry time of about four to five days. This latter feature is useful for travelling artists who work outdoors and may return to a spot a few times over a holiday. Drying matt means that the oil can attract dirt and dust, and thus, if you can it is worth drying your painting as close to the ceiling as possible (cobwebs dusted away). Poppy oil is best used for direct, simple, alla prima techniques rather than complex, multilayered methods which are better done with linseed oil. This is because the oil has a tendency to crack when painted over reactive pigments (this is a key difference between poppy and walnut oil, the latter being less likely to crack when painted over). However, as a crazy sidenote – all this chat about cracks makes cracks seem bad, but are they always? Looking at Harold Sohlberg’s painting of a cabin in the forest, the cracks make the painting, giving it an incredible eerie feel! Just saying! Lastly, poppy oil is excellent if you are just beginning to learn how to make your own paints. It is the easiest oil to make paints with whilst also giving your paints a delicious buttery consistency.

A final point is that the quality of your oil matters. If you are serious, do not, for example, buy linseed oil from a hardware shop, it will be very impure. Similarly, cheaper paints are more likely to yellow and crack than more expensive ones (not to mention lack of pigment) for example Georgian, which is great for students and experimentation, will undoubtedly degrade, yellow and darken with age, whereas the premium brands will not, or are much less likely to do so!

The end, voila, have fun!

By Ned Elliott

Mariella has a breadth of knowledge within the Visual Arts and was awarded her M.A. from the University of Sussex following her post-graduate studies at West Dean College, Chichester. Her passion however is the portrayal of plants. She studied Botanical Illustration under the tuition of Anne-Marie Evans at the English Gardening School in Chelsea Physic Garden, London.

She went on to become a tutor of the subject teaching at both the English Gardening School and West Dean College as well as running workshops at numerous venues, including The Wallace Collection, Sarah Raven’s Cutting Garden, The Museum of Garden History, The Eden Project, The National Trust as well as private groups.

She has exhibited both in the United States of America and the United Kingdom and has paintings in both private and public collections. She is a member of the Chelsea Physic Garden Florilegium Society, an organisation which is in the process of documenting the historic collection of plants within the garden.

Zack started making his paper and wood birds after experimenting with his own Children’s book in which a little boy makes a bird lantern out of old book pages and willow sticks. After struggling to envisage what it would look like He went about making his own as a prop to draw from, this sparked something and after much playing and experimenting Zack made more and more detailed birds over the years, detail is his obsession.

Each bird takes anything from 30 – 120 hours to create, Zack takes great pleasure in creating each bird as realistically as he can, from the first drawings to the last stroke of paint every little feather is lovingly crafted. Pop over to his Instagram, (tab on the left) to get an idea of how much work goes into each bird.

Sadly, we were unable to showcase any of Zack’s incredible birds as he is off on an exciting adventure to Alaska and Mexico where he will be taking his paper and wood creations. We are lucky to have two of his limited-edition prints ‘Hummingbirds’. We hope to have some beautiful handmade birds for you to see in our gallery soon.

www.paperandwood.co.uk

Mandy Hudson lives and works in London. She studied at Maidstone College of Art (KIAD) and has shown in group exhibitions in the UK and internationally. These include Re-Assemble at Collyer Bristow Gallery 2019; The Marmite Painting Prize in 2016; Flowers of Romance, White Conduit Projects, London 2015, MK Calling at the Milton Keynes Gallery; One Day, Gallery Korridor, Reykjavik and The Contemporary Art Societies Art Futures at the Bloomberg Space in 2007.

She has frequently depicted plants in her work. Originally these were specifically in an urban enviroment; weeds growing out of cracks in pavements, small trees on waste-grounds, office plants and flowers in windows.

More recently she has been focusing in on the plant-forms themselves. On short trips out of London she has spent time making small watercolour studies of individual plants, working these up into oil paintings and prints in her studio.