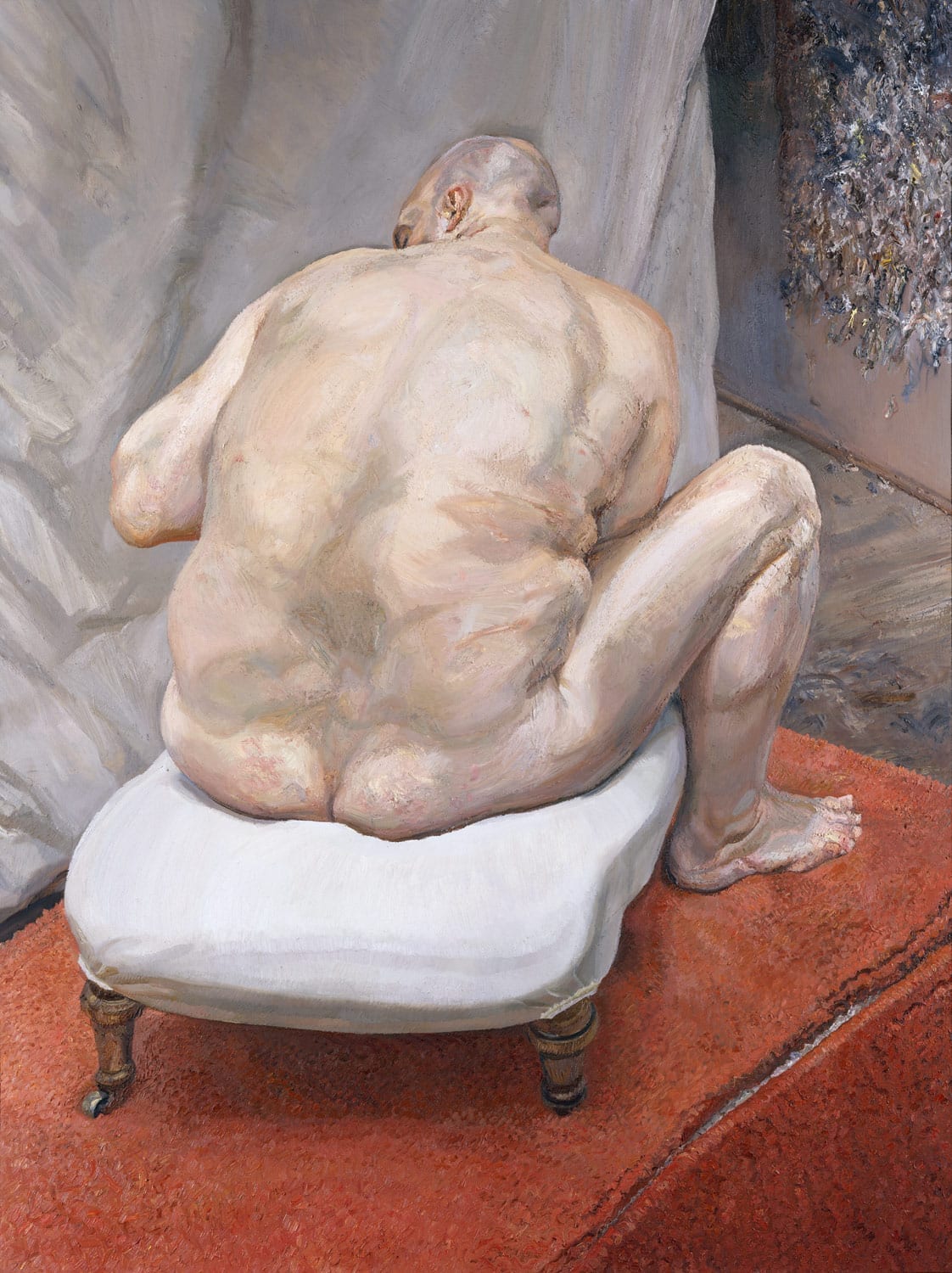

(Naked Man, Back View – Lucian Freud – Metropolitan Museum)

As an artist one is regularly presented with certain scenes to capture; the leaden skies of an overcast England; the sun-soaked shores of a far-away and better place; or the difficult to capture but beautifully poignant spectacle of a melting snowman’s face slowly curling down to a tragic frown. What we all need in these circumstances is a bit of white! But what’s the difference between the three main types, lead white, zinc white, and titanium white?

First, lead white. It is one of the earliest recorded manufactured pigments. As a pigment it is top notch! It is split into two main variants; cremnitz and flake white. These two have slight differences but both are favoured for their durability, pleasing tonal characteristics, excellent opacity and impasto quality. Famously, Lucian Freud was a devout fan – in overloading his canvas with the heavy, granular and milky-hued paint he rendered skin in a rainbow of fleshy nuances. His intense depiction of the nude simply would not have been possible without lead white. But like most good things there is a less-good side – you can’t brush your teeth with it! It will poison you and drive you mad! Don’t do it (unless given license by English Heritage etc.) Thus, due to its toxic nature it cannot readily be considered for contemporary use. Alternatives to mimic lead white exist in Michael Harding’s warm white lead alternative or Charvin’s flake white hue.

Zinc white then, is one non-toxic alternative to the relegated lead. Whilst lead white is milky, opaque, and poisonous zinc white is snowy, transparent, and healthy! Also known as Chinese white, it is a colder, bluer white with 1/10th of the tinting power of titanium white. This transparency means it compliments other transparent pigments and unlike titanium white it does not immediately change a colour to a pastel hue, thus it is perfect say for painting the faint wisps of your granny’s white hair. But beware, in oil it runs the risk of making brittle, hard films and as such zinc white generally finds its home in aqueous mediums where it is free from such defects and is muchly treasured by watercolourists.

Last of the three examined here is titanium white. It is extremely inert, highly durable (resisting temperatures of 1500 farenheit – hot!), is opaque, has excellent covering power and has the best tinctorial effect of any of the whites. Nowadays it is the standard white to go for when dolloping on the palette and is a good non-toxic alternative to lead white though like zinc white it is a colder, bright white bluish hue. When mixed with another colour it dramatically lightens it meaning it can be over-bearing at times – unlike zinc white which gives you more control. As another alternative in oil there is titanium-zinc white, a mix which combines the softness and opacity of titanium white with the transparency of zinc.

In essence, lead white is the ancient favourite but nowadays is scorned for its health implications, zinc white is valued for its unique transparency and titanium is understandably liked for its non-toxic child friendliness, excellent opacity and superior tinctorial power. The latter two are very distinct but are both useful for the artist. Nothing’s perfect and as such there is no entirely perfect white for universal pigment use.