Pictured is Helen Frankenthaler in her studio

For a long, long time oil-primed linen was the go-to painting surface for painters. This all changed in the mid-twentieth century when acrylic paint was invented and began to be used on a surface of acrylic-primed cotton. Within a few years, this combination of cotton and acrylic primer, which made for a cheaper alternative to oil-primed linen, quickly became the most popular and commonly found form of painting support in art shops across the world. Due to this the tradition of painting on oil-primed linen has become slightly more niche. Due to the dominance of acrylic-primed cotton today, there is some feeling that the benefits of painting on oil-primed linen are being forgotten, so this blog will hope to address that and encourage you to give oil-primed linen a go if you haven’t already, whilst also reconsidering primers and supports as a whole.

THE SUPPORT

The material upon which an oil or acrylic painting is executed is divided into two parts, the support which is the cotton or linen, and the actual surface which is the primer. We’ll first look at these supports.

COTTON

Cotton duck, as it is called in art shops, is made from the cotton plant and it’s nice, soft, and fluffy lil’ fibres. “But why is it called cotton duck?”. The term “duck” can be traced to the Dutch word “doek”, which means a linen canvas once used for sailors’ trousers and jackets. “Cotton” has since been added to modern duck items simply to distinguish them from traditional linen duck, though of course, you will note, no one really calls linen “duck”. Cotton is widely produced being grown across Africa, the Americas, and India. Being so widely produced, it is much cheaper than linen which is made from the flax plant nowadays mainly grown in Belgium, where labour is more expensive. Importantly, being cheaper, does not necessarily mean it is an inferior item.

The texture of cotton is regular and consistent, slightly bobbly, some might say it seems a little flat and mechanical, and it comes in a variety of weights too – on the roll at Green and Stone, it is available in 9oz and 12oz. 12oz is generally preferred as it is stronger and has a tighter weave. Importantly, even at 12oz cotton duck canvas is generally thought to be not as strong and durable as linen, although it is still extremely stable. The regular texture of cotton weave produces a fabric that is easy to pull in opposing directions. There is some disagreement over whether this means cotton is better or worse for stretching. Ralph Mayer, a fairly old school but extremely well-informed expert on all things art materials said it ‘stretches poorly; and is ‘entirely inferior to linen’. On the contrary, another writer says that cotton, being more elastic than linen will stretch more beautifully as its elasticity means it will not sag or wave whereas linen, being made of flax, which is a more rigid fibre, is stiffer and if stretched badly can pucker and has to be re-tightened again. However, because cotton is not as strong as linen, from experience, I think I have seen many more easily dented and torn cotton canvases than linen ones and I think this is one of the problems Mayer is hinting at. I think the thing to conclude here is that being more elastic cotton canvas seems easier to stretch and is more forgiving than linen, so if you are a beginner it is good for practice as its cheapness means you won’t make any expensive mistakes. This is in contrast to linen which requires good stretching technique. When stretched properly, linen is undoubtedly stronger and longer-lasting and if it needs re-tightening that isn’t difficult – just wack in some wedges.

The cheapness of cotton, being on average about a third of the price of the same amount of linen, is one of its key advantages for the painter, as it can be used for countless sketches, studies and full-scale paintings without breaking the bank. The colour of cotton is another quality some painters like. Cotton has a lovely soft cream colour which when painted on without primer can really add to a painting (more on this at the end).

LINEN

One of the things people love most about linen is its bold texture which is irregular and natural looking, and because of its use over the centuries, it is more easily associated with great paintings created throughout history. Is the love of this unique texture just a case of linen snobbery as some have suggested? I have no doubt the texture of linen is more characterful than cotton – it certainly adds an additional voice to your painting, especially because it comes in such an array of textures, from the smooth which is popular for portraiture to very rough, almost hessian like texture (think Walter Sickert). There is a sense of organic craftsmanship in its making that is not there in cotton. The other good thing about linen is that, like oil primer, it has been used for centuries, and so we know it is going to last, and last well. Legend has it that linen canvases stretched on wooden frames were first used for paintings of religious subjects to be carried through the streets of medieval Italy, and from there came everything else.

One final point to note before looking at the difference between the primers is that arguably, the cost of linen compels the artist to make a great painting, or at least put more effort into it. Also cotton, being cheap, will often (not always) come with a low quality prime, and so a linen, being expensive will come with a high-quality prime. There would be no point in putting a bad quality prime on a beautiful piece of linen.

THE PRIMERS

So, now onto the primers. The general rule of thumb is …

YOU CAN PAINT IN BOTH OIL AND ACRYLIC ON ACRYLIC PRIMED CANVAS

BUT

YOU CAN ONLY PAINT IN OIL ON OIL PRIMED CANVAS

Of course, you might be an unruly sort of artist who doesn’t care for these rules, but beware you are risking the longevity of your painting!

ACRYLIC PRIMER

The great thing about acrylic primer, just like cotton, is that generally speaking it is cheap, and the second thing that is also great is that you can paint acrylic paint on it which a marvellous medium in itself, which is good because, like I said earlier, you can’t paint acrylic on oil primer, because it will flake off – it is quite literally like mixing oil and water, although confusingly you can paint oil onto acrylic primer because of the absorbency of acrylic primer. As well as being cheap it is easy, non-toxic, and generally odourless, this is because your dilutant is water and the drying time is quick, unlike oil which requires solvents for cleaning and a long drying time.

Sadly, because acrylic primer is generally made cheaply, the quality isn’t always the best and so the most common complaint about acrylic primed cotton, usually when painting in oils, is that acrylic primer is too absorbent. Being too absorbent acrylic primer can make oil paintings dull by drawing in all the oil, leaving flat, lifeless paint surfaces. I think this is another reason why Ralph Mayer was so disparaging of acrylic primed cotton. Thankfully, the problem is not insurmountable. Michael Harding has specially formulated a non-absorbent acrylic primer which has just enough tooth to be able to create a strong bond between the applied layers of paint. With this primer your colours will not sink and will look as fresh as they did the day you painted them. This primer is especially top notch because it can be painted over cheaply primed canvases to render them totally swish!

Another complaint about acrylic primer is that the colour of the ground is too bright a white. With oil painting ground, the colour is often subtle and slightly warm, with a hint of a buttery yellow tint – this is especially true for older painting grounds which were made with every artist’s greatest desire – lead white! (For more information on white pigments see my other blog post – https://greenandstone.com/blancety-blanc-the-truth-behind-white-paint/) One simple way of partially dealing with this is by either tinting your acrylic primer (if you are doing it yourself) with a pigment or paint, or simply washing a colour like burnt sienna over the top of the primer.

OIL PRIMER

Oil primers are meant for oil painting – and that is OIL PAINTING ONLY! Oil primer creates a slippery surface with no absorbency. Being slippery the paint can be moved around and manipulated very easily. Being non-absorbent, the paint does not sink into the primer, and instead shows off colour in all its glory. Indeed, on acrylic surfaces it can be hard to move around oil paint so much without creating a muddy surface, especially because once paint is applied to acrylic primer a stain usually remains, whereas with oil primer the paint can be wiped off almost completely without so much as a smudge. It is this non-absorbency that really sets oil primer apart – the paint truly looks delicious on it, and should look just the same in twenty years as when it was freshly applied. Yum! This is in contrast to painting oil on acrylic, which can appear to go flat even overnight. Of course, this does not apply to when using acrylic on acrylic. Indeed, I remember clearly an old lady oil painter who came into the shop and had only ever used acrylic primed cotton, I suggested she try oil primed linen, and yer know what, she came back and was hooked because the colour remained so true.

The other thing to note about oil primer is that we know what it will be like in 500 years. Most likely it will be in excellent condition, perhaps a little stiff, perhaps with a yellowed varnish, and some cracking to the surface, but ultimately in a very good state. We do not know what acrylic primer will be like because it only started to be used about sixty years ago.

NO PRIMER?

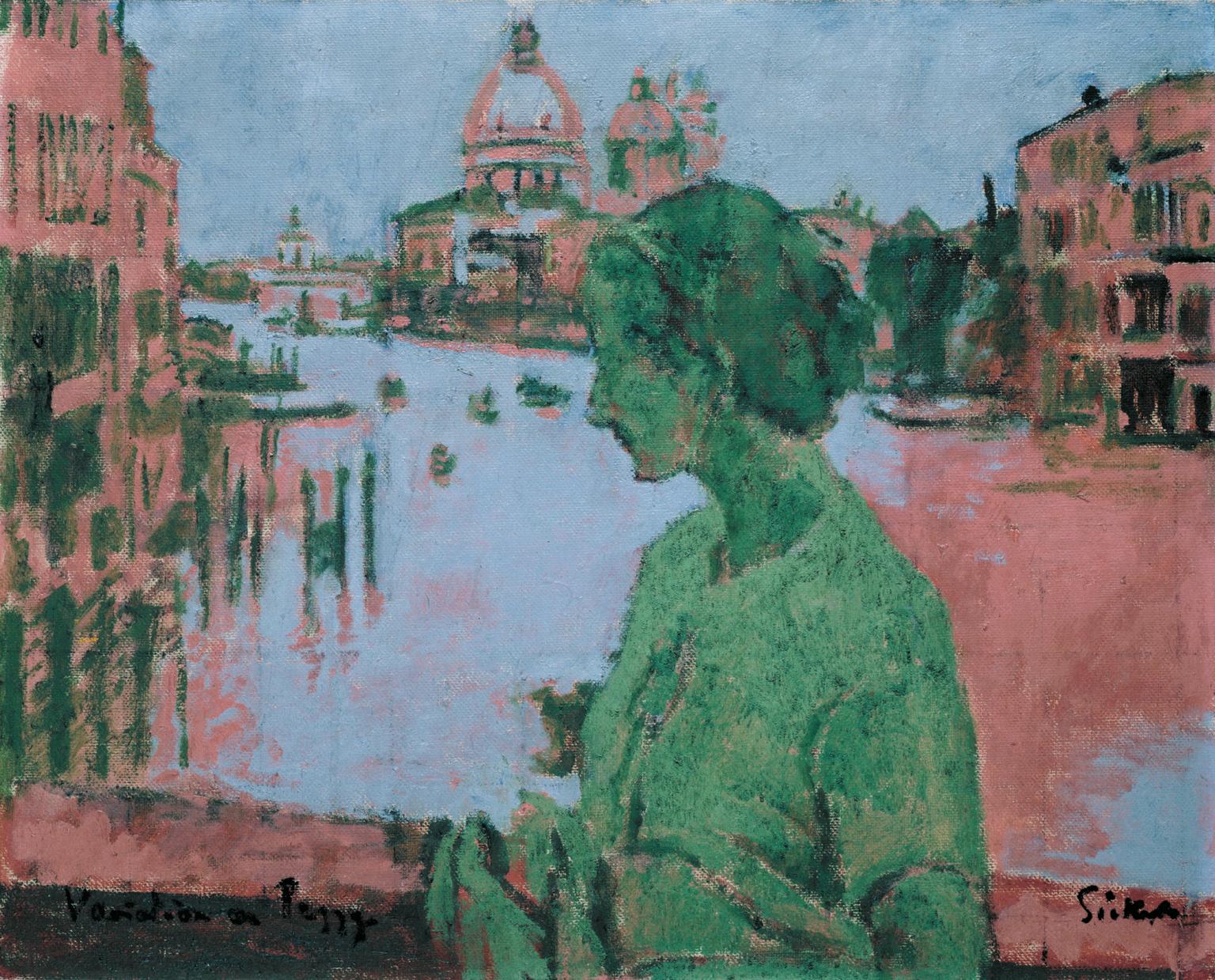

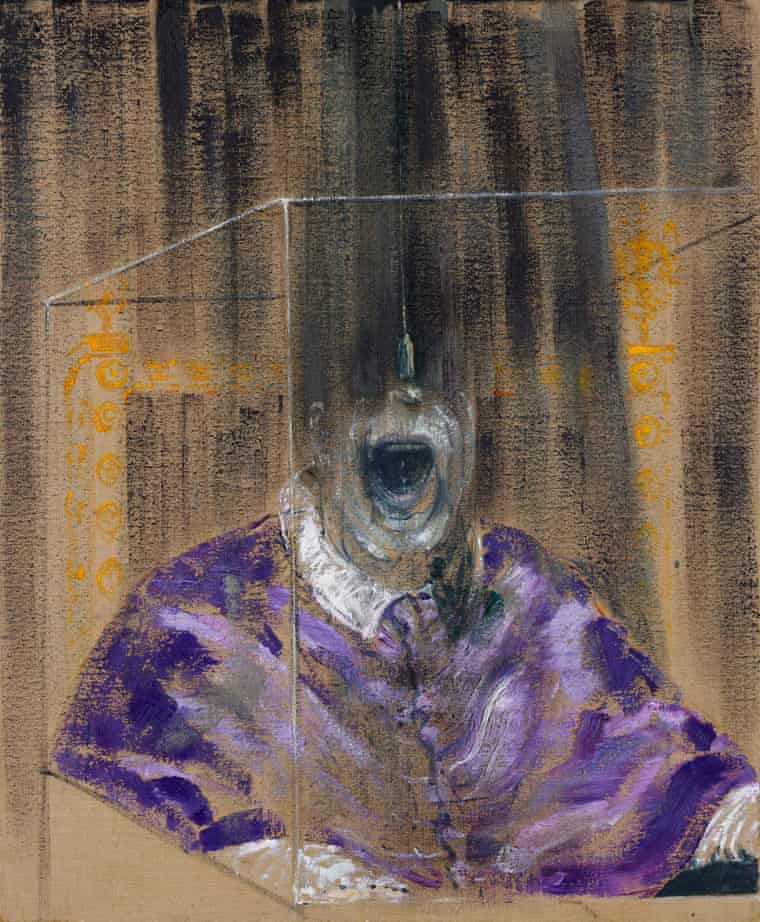

Earlier I provided the rather square general rule of thumb regarding primers and paints. Some artists of course, do not care for these rules. Helen Frankenthaler, for example, used unprimed cotton when she made her soak-stain oil and acrylic paintings. By using unprimed cotton Frankenthaler emphasised the flatness of the painting to her advantage. She created great fields of abstract colour which so far have stood the test of time! As she said, “There are no rules. Go against the rules or ignore the rules”. Technically, by using oil on unprimed canvas Frankenthaler has risked the longevity of her canvas because oil will eventually rot the canvas, but how long that will take is not clear. Another artist who almost always used unprimed canvas was Francis Bacon, an artist regularly referred to as the greatest of the 20th century. Bacon used the warps and roughness of unprimed linen to alter the distribution of oil paint and thereby help create the look of his often violent and deformed paintings. Being unprimed also increases the absorbency of the material, so the colour of paint appears flat, which in Bacon’s case often adds to the impending sense of doom and darkness so present in his work. As shown by both Frankenthaler and Bacon, it is OK, and often brilliant to use unprimed cotton and linen.

CONCLUSION

Before ending, and summarising this rather lengthy post, I think it is important to remember that cotton and linen and acrylic and oil primer are not the only options for surfaces to paint oil and acrylic on. There is also jute, cardboard, paper, wood, your wall, anything really. Picasso, Constable, Toulouse Lautrec, Basquiat, all painted on unusual and unorthodox surfaces – sure, they’ve caused real problems for conservators, but it just shows there are no limits to artistic expression. Ultimately, it is all a question of taste and budget!

By Ned Elliott